Well.

First of all, if you’ve had an email saying that your paid subscription was cancelled, don’t worry. I am not intending to write any paid-only posts until at least January.

Back in June, I wrote that I was working on the draft for a book, and that I would give myself till the end of September to complete it. I tried to stick to a strict schedule of one post a week. Because I had spent the previous month agonising about the story’s order, I decided to simply start writing events chronologically, with a couple of pre-arranged flashbacks. I then set up a paid tier because it was the only way on Substack to keep some of these rather rough posts from being available for anyone; though, of course, they’re still available to anyone who pays. I added all my existing free subscribers to the paid tier at that point, for a limited time, because it felt unfair to suddenly shut people out.

It might have been kinder to do so, because the subsequent posts were of variable quality. The second one, in particular, was a monster; a huge, rambling account of my first ever saola-focused field trip in 2007. It started off well, with a description of a Siberian rubythroat on an island in Hanoi, but I quickly found that far more had happened on that field trip than I’d initially thought and all of it seemed intensely relevant. I didn’t want to drop anything in case it turned out later to be integral to the whole. Old habits die hard. I wrote over twelve thousand words and didn’t even manage to include the intended last scene by the lake. I sent it off without time to read it through; which was a mercy for me but not for my readers.

I kept going with my plan because I knew I’d lose all momentum if I changed it. In August, when I got into what I thought of as the second part of the book, I did diverge but still ended up talking about most of the same things that I’d originally intended to cover in part two. Part three, though, never happened; by the time I ought to have been ready to start it, the end of September had arrived. Also, I was pretty tired.

I was tired in a way that made me, perhaps, a little crazy. I wrote something which started out as an email and ended up being divided into three posts starting with this one about ‘Christianity and Evolution.’ I thought it might buy me time to work out whether what I had was really a book draft, because I came out of the rabbit hole with three weeks of posts. I was intending a new post on the fourth week announcing my intentions, both for the book project, and for this Substack. And then, like a certain NGO I’ve been involved with recently, I took another week, and another, and another.

What I have been doing is restructuring. It’s necessary work if I’m going to pull a story out of this but it doesn’t feel like I’m actually doing anything and it doesn’t feel like I’m in touch with anything either; it’s artifice, but I believe I need to make space for that. As always, I may have that entirely wrong.

I think that I probably do have most of a book here, but I have to do a lot of work to get it in order. I am not quite sure, at the moment, what the relationship with this Substack ought to be. I think that my next major post is probably going to be a re-worked version of that insane 12K word second post. Turns out that it was hard to cut anything out, because my first field trip really did foreshadow everything that came after. I’m hoping to reduce it to about a quarter of the volume and make it into a viable first chapter. Or at least something that it’s possible to actually read through. If I can do that, I’d love to hear what you think.

Before that, I might make some small posts, perhaps including a guide to what I’ve done so far. There are a lot of things I’d like to do on this Substack. I have been abusing it rather, by using it as a place for drafts, but I was wondering if it had run its course. However, just as September was ending, a few people signed on as paid subscribers; actually paying, rather than just getting a free pass. I hadn’t expected any before - the point of this was to find an audience outside my head - but I had hoped. It was a welcome boost at a time when it seemed I’d failed, once again, in what I’d set out to do. I took it as a sign that maybe I shouldn’t close the shutters just yet on this establishment.

I would very much like to know if there’s anything in particular that people would like to hear more about from me. I might be asking some more specific questions about that around New Year.

Audible engagement is as much of a boost as actual money. After my last post, one of my most engaged subscribers said something that made me worry a bit.

is about his smallhold farm in the Philippines. One of the first things he said to me was that he couldn’t possibly do what I do. I look out the window now to the space where I have been failing since at least May to build three small vegetable beds in my little garden. I look back over Leon’s stories of perpetually ‘losing the will to live’ as his little farm variously bloats, devours, withers and straight-up poisons his flocks and structures and visions and sets his labour to naught and he’s still alive enough to be releasing more fanged things into his bloodstream, and not only metaphorically either. I am an ideas man. I’ve tried to be practical but I’m bad at it, and bad at sticking to the plan.So Leon said: “I keep wondering how’re you’re going to finish all this off, is there going to be some positive message at the end?” Then he writes a sad laugh and a sigh and says. “You’re making me question so many things that I never thought twice about.” So I don’t think I can just leave things where I left them. It wouldn’t be right. I mean I questioned all these things and thought about all of these things so much and I failed at what I set out to do.

One of the worst things I used to hear in NGO-world was that “people need positive messages.” That was before Extinction Rebellion existed. In his book about the Yangtze river dolphin, Sam Turvey talks about WWF’s claim to be “restoring the Web of Life in the Central Yangtze” through an ‘integrated approach’ of connecting lakes to the river and ‘working with local government and citizens’ to improve water quality. ‘It made it sound like our work had been done for us,’ Sam comments on page 118; by which point in the book, it is very clear how far from the truth that is.

I have read - even written - so much of this sort of thing, and I think it is really nothing more than advertising copy; just less well-regulated because there’s greater trust. The trust isn’t really deserved any more. The nonsense doesn’t stop after the dolphin appears to be extinct, and it won’t for the saola either. Anyway, whenever anyone talks about ‘people,’ you have to wonder why they’re not saying ‘we.’ “People need positive messages,” ends up meaning: “our customers want positive messages and will pay us for them.”

I have mentioned a couple of times the workshop I went on in 2005 with Joanna Macy at Monkton Wyld. Joanna said that she hated hearing a quote attributed to Margaret Thatcher and a phalanx of others: “Don’t come to me with a problem, unless you bring me the solution too.” That’s just an excuse to shoot the messenger.

Nonetheless…

Well, first of all, if there’s no hope you don’t have to do anything. Second there’s a feeling that ‘true art is angsty’, which perhaps encourages proudly dumping your own mess on unsuspecting others; I’ve heard

say this a few times.Back in March, I had finished outlining a ‘trap’ in a series of six posts of which the last - this one - listed possible ways out. Incidentally, I think the best of this series was the one about “why conservationists keep siding with the enemy.” Listing possible ways out of the trap is not the same as giving recommendations or guidance. I have to recognise that my experience does not qualify me to do this. I am an ideas man and I can point out the possibilities. I don’t know what works. I do have an idea what doesn’t work and, if what I’ve written here is going to be helpful to Leon or anybody, I expect it’s going to be helpful by showing that.

Even there, you have to be very careful. Two reasons for that. One of them is that, as I said, I am bad at sticking to plans. It’s always possible that something would have worked if I’d just kept at it and had faith. The other reason is that - well - maybe the trap is just that I’m overthinking all this. Maybe.

With those caveats, though:

A well-made trap can include an apparent escape route which is actually part of the trap. The basic snare is like this: instinct tells most animals that the way out is to pull harder, but this works the trap tighter. That is one way in which traps are different from cages. By the way, traps don’t imply conspiracies: for a trap to be well-made doesn’t mean it was ever designed; biology 101.

So:

I think that, when talking about the right way for humans to relate to non-humans - when talking about the right way forward at all - we tend to be caught in ‘alternatives’ that are actually part of the trap.

So, for example.

I think that, if someone - and it might be me, or it might be yourself - says something like “the problem is that we’re caught in the myth of progress” - well, they do get brownie points from me for saying ‘we' and not ‘people’ - but if their alternative to the Myth of Progress is a Myth of Eden, then their ‘alternative’ is part of the trap. By “Eden,” I don’t mean “the idea there was a time in the past without suffering” but “the idea that there is a blueprint for the world.” That’s not the only thing “Eden” can mean, I know, but it’s what I mean by it here. Actually ‘blueprint’ might be misleading. That might suggest that the problem is ‘too much machine-thinking’ and that you can avoid the Myth of Eden by saying ‘the right way for the world to be is wild.’ But there is no right way for the world to be.

You may know otherwise. You may have received a message from God that said otherwise. If so, I can only question: are you really really sure that’s what it said, and you’re not hearing the voice of your head or your heart or your gut or your culture.

I am distrustful of other things that present themselves as alternatives.

I think that at least most alternatives offered to materialism and reductionism are self-defeating. Rejecting materialism leads people to affirm - or at least suggest - that there is some irreducible essence that makes living things alive and/or human beings different from dumb beasts. Searching for the irreducible is, by definition, reductionist. I think it’s more likely that the problem lies in equating ‘irreducible’ with ‘valuable’ in the first place. I think, to be honest, that “essence” is just a pretty silly concept that a lot of us are weirdly attached to.

I don’t really see the point of complaining that we see the universe, or living things, as “only dead matter” or as “machines.” This is a common claim but I’m not sure what it really means. Maybe this is because some part of me is missing that should comprehend it, or maybe it is because it actually doesn’t really mean anything very much. Living things are, by definition, not dead and only machines are machines. Living things are like machines in some ways and not others, and exactly which depends on what you think defines a machine. Personally, it seems to me that the defining quality of a machine is that it is designed by some intelligence to fulfil some function, and it therefore seems to me that we have actually moved away from seeing the universe, and living things in particular, as machines - though some of us have refused to do this. There may well be other definitions of machine which don’t work this way, but I’m not really sure what they are. Focusing on whether living things really are like machines, or really are dead matter is beside the point. They are concepts that may or may not be useful, depending on what you are trying to do. What are we trying to do?

I doubt it’s a good idea to try and get away from talking about power - or to get away from talking about the nasty kinds of power. I think that it is not helpful to talk about how you see others - human or otherwise - without also talking about how you are able to see them; what options are open to you. The sentence also works with ‘treat’ instead of ‘see.’ I suspect that the reverse is also true, that it is not helpful to talk about how you can see, or treat others, without ever talking about how you actually do so; but I’m not sure that this reverse point needs to be made. What I’m saying is that if you are arguing that the problem is (wholly or partially) rooted in the fact that we have come to see living things, or the universe, as dead matter, or as machines, then it is essential to ask why we thought we could do that, and why we never did it before. If we only see some things as machines, or only some of the time, then why those things, or those times, and not others? Is something stopping us or do we just not want to? It seems to me that at least part of the answer must be that we feel - wrongly perhaps - that we are able to get away with it and that we want to at least some of the time. If that is so, then we apparently have the protection of some power, which may or may not be our own power, depending on how you look at it. And if that is so, then any attempt to redress the problem needs to acknowledge this fact. The Council of all Beings can quickly be dissolved when things get too uncomfortable for the organizers. That doesn’t mean it’s bad to try. Just shouldn’t be naive about it.

I also think we are less powerful than we think we are, but probably not - sadly - because we underestimate the more-than-human world. I think it’s a form of denial to talk about the relationship between humans and nature solely in terms of what ‘we’ want; ‘our’ moral weakness, and the choices that ‘we’ are making. There isn’t a ‘we’ that can make choices because of the thing called ‘the Tragedy of the Commons.’ That name is unfortunate because, despite what the man who coined the phrase believed, there actually are ways to avoid the tragedy that don’t require bowing to a tyrannical Leviathan, and medieval commoners found some of those ways. This is increasingly recognised and celebrated, but it also needs to be remembered that it isn’t guaranteed to happen, or to be sustained. The dynamic of the tragedy is always there, waiting to reassert itself when things break down. If we don’t do it, they will, which means that it will still get done and they will get all the advantages while we get nothing. It can be both self-serving and correct for an American (say) to claim that “the Chinese will do it if we don’t.” I don’t know how we get anywhere, but we don’t get anywhere by pretending this isn’t true. Having an animist outlook, by itself, is a poor defence against this; as I witnessed in Nam Đông.

I don’t think there is a true scale or level of organization: particles, molecules, individuals, nations, species, which is the right one for telling stories, or the right one to focus on.

But…

Why can’t I just go back to the supposedly ‘dominant narrative’ then?

Well that was what Part three was supposed to be about. In lieu of Part Three being written, I think it’s better to loop right back to where I started, with the article in Dark Mountain about the dream and the dragon on the mountain.

Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year, if you don’t hear from me.

Definitely power, I want to know more about that. Seems to me you are on to something with that. Specifically can we think about what the power consists of with regard to conservation biology and whether it’s always on the side of modernity or development or does it sometimes support wilderness or conservation or whatever? Can it be resisted or influenced? There’s a danger of this being a history of protest movements, which maybe isn’t what you are after. Following Fairy Creek Blockade on Instagram, definitely a power struggle there between opposing worldviews, but also between groups of people…. Probably your area is more philosophical than that, but maybe it is relevant.

Also, I agree your emotional responses are interesting and not to be dismissed. But you are very hard on yourself. Would you approach anyone else with such blistering scrutiny? Can you not trust your impulses a bit, sometimes? Is the Oxford lacuna about an absence of compassion for the self?

I have been following from afar, it’s quite interesting seeing the process processing!

Happy Christmas!

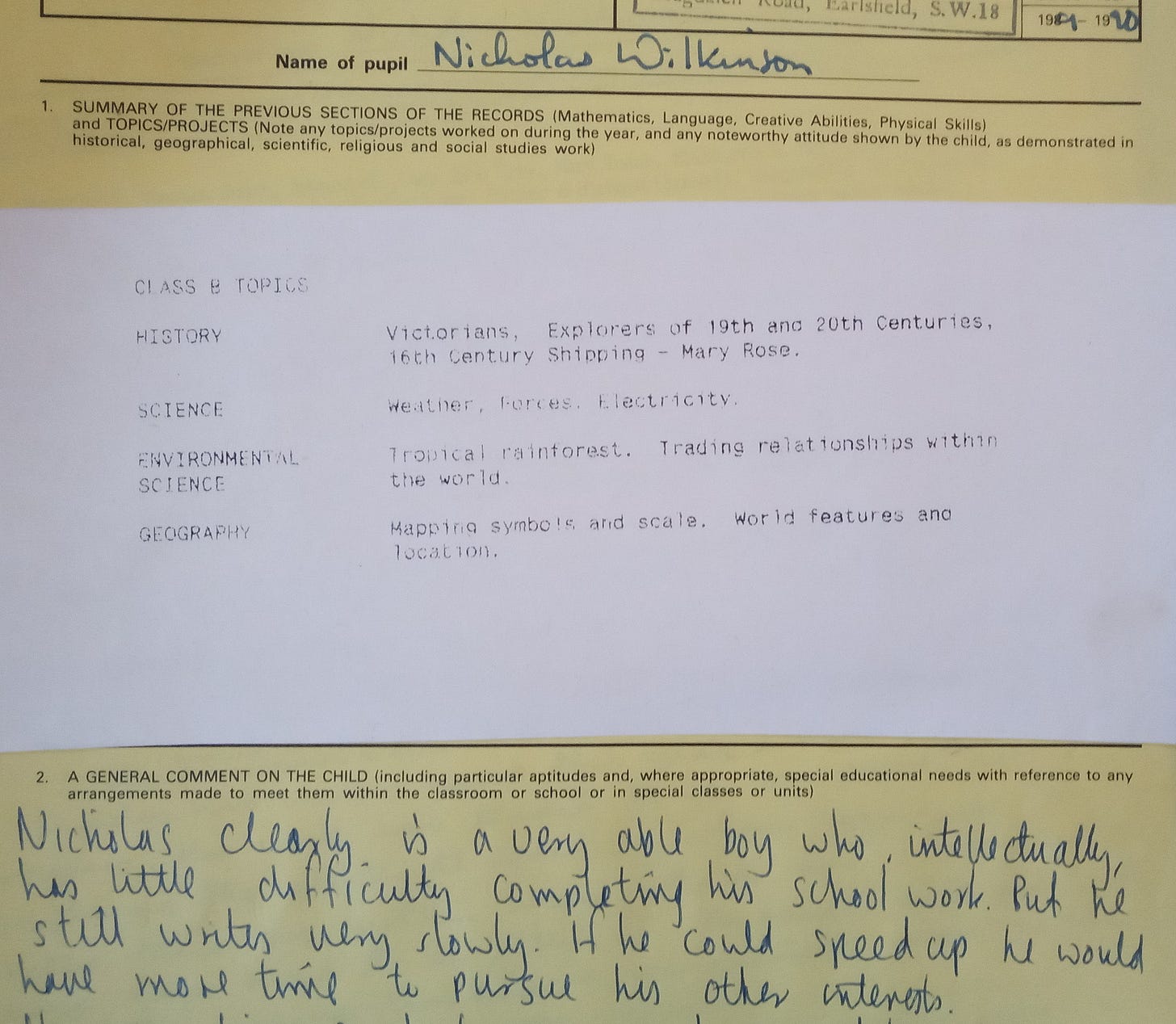

That report card is fantastic. Were you just slow at writing or were you lost in thought planning out some future novel?